Sexual Orientation and Television

Sexual Orientation and Television

Once the freeze on television broadcast licenses was lifted by the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 1952, broadcast stations proliferated throughout the United States. Additionally, the FCC set the regulation standards for the mass production of television receivers. making them relatively inexpensive to produce and affordable for the middle-class American public. Having been a mostly East Coast, upper-class phenomenon before 1952. television broadcasting quickly became an economically profitable industry catering to perceived middle-class tastes.

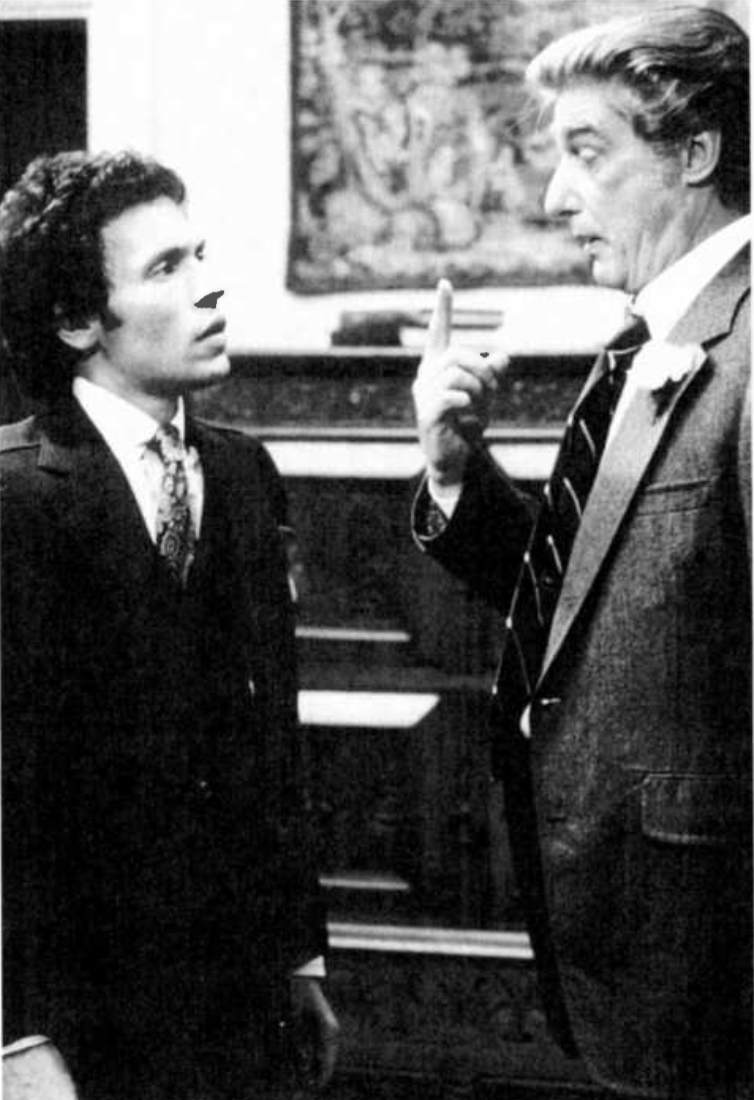

Soap, Billy Crystal. Richard Mulligan. 1977.

Courtesy of the Everett Collection

Bio

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s. the television broadcast networks implicitly constructed the mainstream viewing public as replications of the idealized middle-class nuclear family, defined as monogamous, heterosexual couples with children. In response, the overwhelming trend was to provide programming targeted toward this consumer group. To a large degree, this construction stemmed from the larger context of American society. in which the ideals of heterosexuality and family dominated the overall hierarchy of sexual orientation.

However, this assumption was reinforced because the mode of distribution of programming and the measure of economic success were significantly different for television broadcasting than for most other forms of popular culture. For most other popular culture industries, consumers had to actively purchase a product (a movie ticket. a record. or a book). Economic success and popularity were determined by the number of sales of the cultural product. Within the American broadcasting context, however, the programming was distributed free of charge to anyone with a television receiver that could pick up the broadcast signal. The networks generated profits through advertising, selling the viewing audience as a potential target for commercial messages. In this mode of distribution, a network's success was determined by the number of viewers it attracted, not the number of programs sold. This interaction among the networks, advertisers. and the viewing audience developed into a very complex economic relationship.

Until the early 1970s and the introduction of demographic measurements. the networks quantified a mass audience as an index of a program's popularity to set commercial rates for advertisers. Since most television use by the American public has been and continues to be in a domestic environment. the networks and advertisers easily assumed that the viewing audience in its values mirrored the idealized middle-class nuclear family of the 1950s. Given this institutional construction of the television viewer, the networks produced and broadcast a plethora of programs built around the values and concerns of the contemporary nuclear family. Series such as I Love Lucy, Father Knows Best, Leave It to Beaver, and The Donna Reed Show developed scripts explicitly exploring gender and sexual roles in the context of the 1950s. For example, Father Knows Best often defined appropriate and inappropriate gender behavior as Jim and Margaret Anderson negotiated their marital and implied (hetero)sexual relationship. Explicit discussion of sexual behavior was forbidden. In addition, the Anderson children were groomed for heterosexuality on a weekly basis as they entered into the adolescent dating arena. In the context of the series, same-sex romantic attraction was not offered as a viable or legitimate option for offspring Betty, Bud, and Kitten. Nor did episodes deal with many heterosexual options outside of conventional coupling, limited to traditional heterosexual norms.

Even series that were not located in the contemporary family milieu of the 1950s or 1960s reinforced a narrow range of heterosexual choices. In a series such as Gunsmoke, with its surrogate family, traditional heterosexual coupling was the status quo. What sexual tension existed in the series surfaced between Marshall Matt Dillon and saloon owner Miss Kitty, not between Matt and his deputy sidekick Chester. Even overt sexuality between Matt and Miss Kitty was seldom displayed in the series . After all, how was the wild expanse of the western prairie to be tamed if the product of sexuality was pleasure rather than population growth? Given the baby-boom mentality of the 1950s and 1960s, the sexual orientation of Gunsmoke 's characters and their sexuality replicated the dominant values of American society, at least as they were perceived by network programmers and advertisers.

This perception about sexuality began to shift slightly by the early 1970s as pleasure became more acceptable as the foundation for sexual activity. Even so, sexual orientation continued to be overwhelmingly defined as heterosexual, although an occasional gay or lesbian character began to make an appearance.

Several factors account for this cultural breakthrough. At this time, the Prime-Time Access Rule forced the networks out of the business of program production. As a result, the networks began to license programming from independent production companies, such as Norman Lear's Tandem Productions and MTM Enterprises. These independents were willing to address subject material, including explicit sexual pleasure and homosexuality, that had previously been ignored by the networks.

Additionally, the networks and advertisers began to shift their conception used to market the viewing audience. In the ratings competition between the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) during this same period, undifferentiated mass numbers as the target of advertising and the basis for determining commercial rates gave way to the first wave of demographic marketing toward a younger, urban rather than older, rural audience. In conjunction with the moxie of independent program producers, sexuality, including explicitly gay characters, began to surface in programs because these young, urban viewers, at least in the perception of the networks and advertisers, were less inclined to take offense with potentially controversial topics.

Images of gay men and lesbians began to appear in fictional programming during the early 1970s for another reason as well. Culturally, gay men and lesbians became more visible in American society after the Stonewall riots in June 1969, a date now celebrated as a watershed moment of the modern gay rights movement. As gays and lesbians entered the struggle for social acceptance and legitimization within mainstream discourse, the emergence of gay characters became part and parcel of this burgeoning social conscious ness. In response to a newfound possibility of representation, gay activist groups such as the National Gay Task Force (NGTF), formed in 1973, attacked any outright negative mainstream media images of gay men and lesbians.

Initially, single-episode gay characters, at best self-destructive and at worst evil, were used as narrative plot devices to create conflict among the regular characters of a prime-time series. This was not an acceptable representation for most gay activists. The first major conflict between gay activists and the networks occurred over just such a depiction in "The Other Martin Loring," an episode of Marcus Welby, M.D. during the 1973 broadcast season. The confrontation focused on the dilemma of a closeted gay man worried about the effect of his homosexuality on his family life. Welby's advice and the resolution to the narrative conflict finally rested on the repression of sexual desire. As Kathryn Montgomery (1989) points out, this initial conflict had little effect on preventing the broadcast of the episode. However, it did open the door for continued discussion between gay activists and the networks concerning subsequent representations.

Indeed, the networks began to solicit advice about gay representation before programming went into actual production. By 1978, the NGTF provided the net works a list of positive and negative images that it considered to be of greatest importance. From the negative perspective, the organization wanted to eliminate stereotypically effeminate gay men and butch lesbians as characters as well as inhibit the portrayals of gay characters as child molesters, mentally unbalanced, or promiscuous. In contrast, positive images would include gay characters within the mainstream of the television milieu. These images would reflect individuals performing their jobs well, who were personable and comfortable about their sexual orientation. Additionally. the NGTF asked to see more gay couples, more lesbian portrayals. and instances where gayness was incidental rather than the focus of a narrative controversy centered on sexual preference.

As one manner of achieving these positive goals. gay activists suggested that continuing regular gay or lesbian characters be used within a series format, expanding beyond the plot function of a "problem" that needed to be solved and eliminated . However, the inclusion of a recurring gay character created problems of its own. Story editors and scriptwriters had to maintain a delicate balance between creating gay characters who were too extreme in their behavior so as to he offensive to heterosexual mainstream viewers or were so innocuous that they become nearly indistinguishable in their gayness. Several series, beginning with Soap and Dynasty and more recently Doctor, Doctor and Melrose Place, have included regular gay characters as part of their narrative foundation. with varying degrees of success. Often within these series, the gay character is isolated from any connection to a larger gay community and lacks any presentation of overt sexuality. While it has certainly been acceptable for heterosexual individuals and couples to engage in displays of affection. it has been untenable, until recently, for gay characters to activate similar behavior.

Despite this glaring drawback, gay characters as series regulars have functioned differently in the narrative context than in a one-shot episodic appearance. For the most part, recurring gay characters have been comfortable with their sexual identity. The possible exception is Steven Carrington, oil heir apparent in Dynasty, who fluctuated in his sexual orientation from season to season. While a series regular's gayness could still initiate some problems in a series, his or her sexuality was no longer an outside problem. Rather, the series regular could provide a narrative position whereby sexual "otherness" could be used to discuss and critique the dominant representation of both homosexuality and heterosexuality. Contextually. adaptation to rather than the elimination of homosexuality became the narrative strategy.

Despite Dynasty's wavering on the subject of homo sexuality, early installments of the series illustrate this narrative shift. The gay subplots of this prime-time soap opera often performed a pivotal role in exposing the contradictions of heterosexual patriarchy. An excellent example is when Blake Carrington, the series' patriarchal figure, stood trial for the death of son Steven's gay lover. The courtroom setting of this particular subplot created an ideological arena for Steven to critique his father's homophobia. patriarchal dominance, and sense of socially constructed gender roles from an explicitly gay perspective. As can be seen by this example, a gay man or lesbian who appears as part of the regular constellation of a series' cast naturalizes gayness within the domain of mainstream broadcast narratives, thus allowing that sexual otherness a cultural voice of its own. In some instances of this process of naturalization, these fictional gay characters face many of the same problems that their heterosexual counterparts encounter. This has not necessarily meant that their sexual orientation has been ignored but rather that it has been woven together with other concerns to create multidimensional, sometimes contradictory characters that reflect some of the experience of gay men and lesbians in American society.

Since 1973. the broadcast networks. program producers and gay activists have maintained an ongoing working relationship with each other. The Alliance for Gay and Lesbian Artists in the Entertainment Industry, an internal industry activist organization, has provided an important connection with outside gay activists. Of ten. gay men or lesbians within production companies have alerted activists about potential problems with plotlines or characters. Many producers and scriptwriters now elicit opinions from gay and lesbian activists in the preproduction process. thereby circumventing costly confrontations once a production is under way. In addition, network broadcast standards and practices departments have internalized many of the activist's concerns and criticisms. thus pressuring program producers to eliminate potential trouble spots from scripts. The activists have also learned to praise producers. directors and scriptwriters creating appropriate gay themed programming with positive reinforcement. such as yearly awards and congratulatory telegrams, letters. and e-mail messages. Because of this de facto system of checks and balances. antagonistic confrontations seldom arise between gay activists and the television broadcast industry.

The gay activists' success in dealing with the networks and program producers has also activated a strong response from religious and political conservatives since the mid-1970s. As Gitlin (1983) argues, these conservative social forces have regarded the social inroads made by gay men and lesbians as a threat to their own social power and deeply embedded patriarchal values, including traditional conceptions of the family, gender roles, and heterosexuality. Any positive representation of homosexuality (or even bisexuality) undermines the legitimacy of these traditional values. The conservative far right has been dominated by religious fundamentalist white males such as Jerry Falwell and Donald Wildmon as well as white antifeminists such as Phyllis Schlafly. Indeed, Wildmon heads the American Family Association (AFA), a formidable advocacy organization that monitors the television broadcasting industry's presentation of sexuality with a Bible-thumping fervor.

In contrast to the gay activists who have been more than willing to confront the networks and program producers directly about the representation of sexual orientation, the AFA has employed an indirect approach. Providing members with postcards pre addressed to advertisers, the AFA has often threatened a boycott of consumer products manufactured by companies placing commercials within the broadcast of objectionable programming. While the direct preemptive approach of the gay activists appears so far to have been more successful with the commercial networks than the post broadcast method used by the AFA, the latter organization·s efforts have produced some effect. For one thing, advertisers who have come under fire from the AFA have begun to consider placement of a commercial in potentially objectionable programming less lucrative than they might have previously.

As a response to advertisers' reluctance to place commercials in programs that include a positive discussion of homosexuality, the networks' broadcast standards and practices departments have codified some of the AFA's concerns about sexual orientation as a means to counter any negative criticism from conservative advocacy groups. For one thing, the positive portrayal of any physically romantic or sexual interaction between gay or lesbian characters has been exercised, generally, from programming content. In addition, any gay-themed script must include at least one character who presents a critique of homosexuality to provide a balanced discussion of the subject. As a side note. the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (GLAAD). formed in the mid- 1980s, has appropriated AFA's practice of sending out pre addressed postcards . GLAAD has also urged individuals to send them to advertisers, praising their bravery in placing commercials in gay-themed programming.

At times, program producers and the networks have ended up at the center of a cultural tug-of-war between gay activists and conservative religious fundamentalists. Perhaps the best illustration of this predicament occurred in the summer of 1977. The American Broadcasting Company (ABC) had scheduled Soap for the fall lineup. The series was created by Susan Harris as a satire on both the nuclear family and the overdrawn angst of daytime drama. One of the regular characters was Jody Dallas, a gay man. In addition, the heterosexual characters engaged in a number of extramarital affairs, hardly reinforcing traditional monogamy. ABC previewed the initial episodes of the series for local affiliates and gay activists. Some disgruntled station owners alerted the National Council of Churches, the forerunner of the AFA, about the risque content of the show. In addition, the conservatives felt that the inclusion of Jody Dallas condoned homosexuality. As a result of the conservative backlash, some affiliates refused to carry Soap. Conservative forces picketed stations that did air the satire. Under threat of a product boycott, several potential sponsors backed out of buying time in the series. Gay activists were not pleased with the premise of the Dallas character either. He was too much the gay stereotype. In addition, Dallas was not particularly satisfied with his sexual orientation as he planned a sex change operation.

In an attempt to appease both sides, Soap's producers adjusted the series after the first few episodes. Dal las's stereotypical elements were modified, nearly neutering the character in the process. In comparison to the other characters, his behavior became less explicitly sexual. Even so, he became more affirmative about his sexual orientation, dropping any desire to change his gender. Ironically, the more stable, less sexually outrageous Jody Dallas seemed to address conservative concerns about homosexuality as well. Without the overt presentation of Jody's sexual desire, apparently religious conservatives believed that the series did not condone homosexuality as strongly .

Throughout the 1980s and into the 1990s, opposing gay and conservative advocacy groups have continued to pressure the networks, program producers, and advertisers on the parameters of representation about sexual orientation. As in the case of Soap, gay and lesbian characters have usually appeared in a highly diluted form. nominally gay with perhaps a political stance but lacking sexuality. Only in a very few instances have these limits been successfully challenged, most notably in an episode of Roseanne, a domestic sitcom, and Serving in Silence: The Margarethe Cammermeyer Story, a made-for-television movie. In both instances, the cultural and economic clout of their respective production companies provided the impetus to include moments of intimacy and sexuality for lesbian characters. During the spring of 1994, Roseanne. as reigning prime-time diva and executive producer of her series, threatened to withhold an episode from ABC if it did not air with its lesbian kiss intact. The network initially balked but eventually broadcast the unedited episode rather than lose potential commercial profits from a top-ten series. The combined talents of Barbra Streisand, as executive producer, and Glenn Close , as additional executive producer and star, added production muscle to Serving in Silence. With their involvement, NBC gave the movie, dealing with both Cammermeyer's fight to be reinstated into the military as an open lesbian and her blossoming romantic relationship with her lover Diane, a green light. With Streisand's and Close's involvement providing an aura of quality and legitimacy, this production opened the cultural space for moments of physical intimacy as integral narrative elements. Roseanne and Serving in Silence have been hallmarks in the presentation of gay and lesbian experience in American television broadcasting.

A watershed of sorts was reached in the 1996-97 broadcast season. On Ellen, a series based around stand-up comedienne Ellen DeGeneres, a number of early episodes dropped thinly veiled innuendos regarding main character Ellen Morgan's sexuality. For example, while shopping for a house, Morgan agrees with her real estate agent that a walk-in closet was as large as some apartments but that she would not want to live in it (which could be construed as a reference to being "in the closet," that is, hiding one's homosexuality). Writers peppered the series that season with double-entendre teasers, especially targeted for lesbian and gay viewers "in the know" about DeGeneres's own sexual predilections. By March 1997, rumors became public knowledge as DeGeneres confirmed both her own status as a lesbian and the production plans to bring her sitcom character out of the television closet. Though initially reluctant to give the go-ahead for such an episode, ABC set the air date for "The Puppy Episode" for April 30, 1997.

Despite aggressive attempts by the AFA and other conservative social groups to promote a boycott of Disney and ABC, the broadcast of "The Puppy Episode" was extremely successful, garnering the highest ratings for Ellen or any other regularly scheduled series on ABC for the 1996-97 broadcast season. At this historical juncture, ABC's promotional support, in conjunction with the overwhelming endorsement from other popular culture venues, did seem to promote the belief that "naming" oneself as gay was perfectly acceptable. "Behaving" gay became another issue altogether, as the conflicts between ABC and DeGeneres over program content and parental warnings in the fall of 1997 erupted into very public disagreements. When DeGeneres pushed for an on-screen romantic relationship that included a kiss, ABC balked. The very public conflict took its toll on comedienne DeGeneres as well as the overall tone of the series. By spring 1998, Ellen's popularity had plummeted in the Nielsen ratings, the only measure of success that really mattered to the networks . The series was canceled in a flurry of public accusations and recriminations .

With this programming incident freshly embedded in both the networks' and the public's consciousness, NBC's inclusion of Will & Grace, another gay centered sitcom, in its autumn 1998 Thursday night "must-see TV" lineup was somewhat surprising. Initially, Will & Grace's narrative foundation was built on the enduring , and endearing, relationship between Will Truman, a gay man and successful lawyer, and Grace Adler, a heterosexual woman and his best friend since college. However, caustic secondary characters Jack McFarland, Will's outrageous and self-centered gay friend, and Karen Walker, Grace's wealthy, substance using secretary, provide foils and broad contrasts to the title characters• relatively more level headed (read "mainstream") actions. Whether because of or in spite of the explicit "gayness" of the series, it has garnered audience favor, critical approval, and television industry esteem, with a number of Emmy wins. Indeed, that elusive on-screen gay kiss came to fruition during the series' second season. When Will and Jack are disappointed when a heavily promoted kiss between two men on a fictional NBC series fails to materialize, the two march to network headquarters to protest. Though brushed off by a closeted public relations denizen, they enact their protest-a lengthy kiss-in front Al Roker, The Today Show weatherman, as he broadcasts live in front of Rockefeller Center.

Even so, broadcast television has yet to include a gay kiss that encompasses either a romantic or a sexual punch. However, given Will & Grace's continued success, the potential for such a momentous event looms on the horizon in broadcast television. In contrast, the American version of the British series Queer as Folk has moved far beyond the passionate same-sex kiss to include presentations of relatively frank depictions of sexual interactions. However, those depictions tend to be less frankly graphic than those presented on the original U.K. series. In addition, the 15-year-old sexually active gay teenager in the U.K. series appears as a 17-year-old in the U.S. version.

While gay men and lesbians inside and outside the television industry have applauded these cultural steps forward, the gains are by no means secure, especially outside the commercial networks, where gay activists have less social and economic power. In the American social context of the 1990s, the struggle between gay rights activists and anti-gay rights advocates has reached a crescendo. Both sides have confronted each other over the legitimacy of sexual orientation in the political and legislative arenas, with neither side winning any clear legal victories. However, a conservative a shift has occurred in the political arena that could drastically impact gay and lesbian representation in non commercial American public broadcasting. Because the federal government economically supports non commercial broadcasting, funding for the Corporation for Public Broadcasting (CPB) can be reduced or eliminated altogether through the agendas of powerful political interests. Therefore, proactive intervention (techniques used by groups such as GLAAD with network representatives, program producers. and advertisers) has not worked as well in the noncommercial broadcast setting.

Once the bastion of liberal tolerance and a cultural podium for marginal social groups, the CPB has increasingly come under attack from conservative forces in Congress for precisely those reasons. Conservatives have threatened to eliminate funding and privatize CPB in response to the use of federal tax dollars to produce nontraditional programming, especially programming targeted to the gay community. Special programming such as Marlon Riggs's Tongues Untied. an exploration of gay African-American men·s experiences with both homophobia and racism, and Masterpiece Theatre's production of Armistead Maupin's Tales of the Cit): a narrative set in the 1970s San Franciscan milieu of sexual experimentation, have been specific targets of conservatives. Both productions contained a fair amount of frank, adult language about sexuality and a modicum of nudity. Indeed, many Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) affiliates refused to air either program or, if they did broadcast the offerings, censored the material radically. Tales Of the City generated enough controversy that conservative forces were able to pressure CPB to withdraw funding for the sequel, More Tales Of the City.

As the social and political struggle over legitimization of gay rights accelerated in the mid- 1990s. the inclusion and representation of gay men and lesbians in entertainment television programming continued to be a point of cultural conflict. Driven by the economic demands placed on network broadcasting as it competes with the relaxed standards on cable channels, programming broadened the parameters of acceptable content. Thus, the economic demands of commercial television may create an atmosphere for further presentation of alternatives to monogamous heterosexual orientation. In addition, the gay community has gained more interest from advertisers as a demographic social group with relatively more disposable income to spend. In deed. some manufacturers of products. such as clothing. alcohol, and travel, have begun to produce print ads directly targeting gay men and lesbians. Similar advertising in television programming, specifically attracting a gay audience, is probably not far behind. In contrast, the strong shift to the conservative right in the political arena has already imposed government regulations on funding for the arts. The federal government has placed limits on the range of appropriate subject matter for grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the National Endowment for the Humanities, and even the CPB. It is not outside the realm of possibility that conservative political forces will also attempt to regulate commercial television programming content.

With the proliferation of cable television distribution, however, such efforts might meet with limited success. The huge-and largely unexpected-2003 success of Bravo's Queer Eye for the Straight Guy indicates not only that there is an audience within the gay communities for material related to gay experience but also that a considerably larger audience will attend to gay-themed programming. This program, in which five gay men ("the Fab Five") engage in a "makeover" for a straight man, may have seemed a risky venture for the small network when it was acquired by NBC. Within weeks, however, word of mouth as well as mainstream press and electronic media publicity made the series sufficiently popular-and safe-for episodes to be presented on NBC's main schedule. By January 2004. Bravo announced that Queer Eye would go "on the road to Texas" for additional episodes, and the five cast members had negotiated for substantial raises.

As was the case with Ellen and Will & Grace, responses both within and outside the gay communities were mixed. But it seemed clear that such programs would no longer be taboo from the first proposal. Given the larger context, issues about sexual orientation are hardly going to disappear in the near future. If anything, despite the success of a small number of programs, the number of confrontations over sexual orientation and the intensity of those conflicts will only increase.